Do public school students have the right to prospectively opt out from encountering a book, specifically one that contains LGBTQ+ materials and themes? Yes, according to SCOTUS, who just decided Mahmoud v. Taylor, in favor of parents who objected to a Maryland school district making books available to teachers and students for classroom use and extracurricular reading. These books were not mandated in classroom curricula. As a result of the decision, parents can demand that their children be pre-emptively opted out from encountering these books. You can read more about the case at Lambda Legal.

We at Mama’s Got a Plan think it’s a grand idea to have books that reflect all students. So here is our review of the seven books in question, complete with spoilers. Wikipedia kindly listed them in grade order … so here we go!

Pre-K: Pride Puppy, by Robin Stevenson

An overwhelmingly happy and rainbow-filled ABC book celebrating many positive values – neighborliness, parades, farmers markets, families, dogs.

This is exactly the sort of book to turn a MAGA brain into whipped cream. So many supportive representations of queerness! We find it pictorially a bit overwhelming, but it is an excellent book to prompt discussion of questions that children may have around LGBTQ identities.

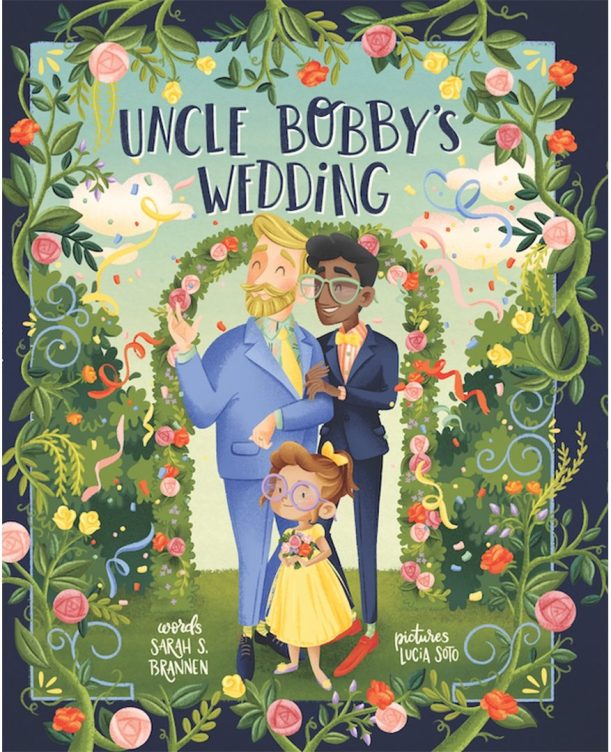

Kindergarten: Uncle Bobby’s Wedding, by Sarah S. Brannen

Chloe’s favorite uncle, handsome and endowed with truly beautiful white guy hair (facial and otherwise), announces his engagement to Jamie, to the great delight of the family. Chloe, however, disapproves because marriage would divert Uncle Bobby’s attention away from her. Bobby promises to always love her, and then Bobby and Jamie together charm Chloe with ballet, ice cream sodas, swimming and sailing, and campfires and marshmallows. Chloe yields in the face of their love and attention, allowing Bobby and Jamie to have a picture book (literally!) wedding that everyone enjoys.

This story is not really about gay marriage, but about children dealing with fears of losing the attention of favorite family members who enter new adult relationships. If children cannot stand to see a gay couple in a picture book when the gayness of the couple is not even the theme of the book, they’re going to have a very hard time out in the world once they leave their cloistered community – in which gay couples also exist, if only in the closet.

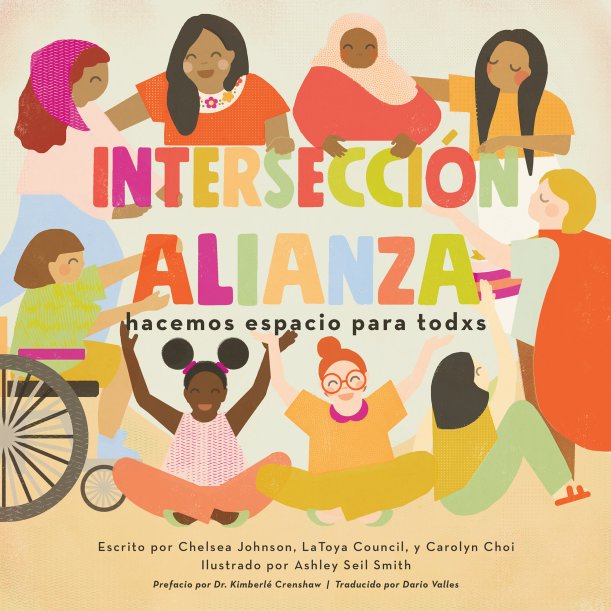

1st grade: IntersectionAllies: We Make Room for All, by Carolyn Choi and Chelsea Johnson

A thorough explanation of intersectionality and allyship, shown through the eyes of children. Kimberlé Crenshaw, the originator of the intersectionality framework, wrote the foreword. A couple of choice phrases: “We can listen to and support each other in ways that unite us across differences.” “I believe we are strongest when we build communities that are found on the understanding that we have a stake in each other.” Who can argue with that?

A lovely feature of this book is the portrayal of children helping each other, their own families, and one another’s families in situations involving ability status; childcare; gendered clothing and religious garb (hijab); racialized violence (police state); ecology, conservation, and protection of Native Americans; immigrant families, including those fleeing war and violence; language barriers and multilingual families; and citizenship status.

Although listed as a first-grade book, the materials at the end (definitions, notes, and discussion guides) make this an excellent book for children to refer back to as their understanding grows throughout their school years.

2nd grade: My Rainbow, by DeShanna Neal and Trinity Neal

Through the lens of Trinity, the main character, who is Black, on the autism spectrum, and a transgender girl, we see examples truly exceptional parenting.

Trinity feels she needs long hair. The problem is that she cannot stand the feeling of her hair growing out. Her family listens carefully but doesn’t know what to do – until cello-playing brother Lucien comes up with the idea of a wig. Her mother takes the idea even further and stays up until the wee hours creating what Trinity needs. The book concludes with a very happy Trinity and the family expressing love. This one made us sniffle. The book shows the reader that when there aren’t simple solutions, with enough love and creativity and dedication people can find the answer.

In addition, this book engages all the senses with its vibrant illustrations and music running behind the words.

3rd grade: Prince & Knight, by Daniel Haack

The King and Queen feel that Prince – again with the gorgeous hair! – won’t be able to govern alone: the kingdom is simply too big. They travel far and wide to introduce him to various ladies, but “it was soon clear that he was singing a different tune.” When news comes to them that a dragon is threatening the kingdom, Prince races home on his horse. When he is just about to engage the dragon, a knight appears and temporarily blinds the dragon with his shining armor. Prince climbs on top of the beast and subdues it, but in the process is knocked off. Dragons are big, so it’s a long fall, but Knight races on his horse just in time to catch Prince – very romantic! Knight is revealed to be another hot guy with gorgeous hair, and the two men immediately fall in love. Upon returning home, the two lovebirds are accepted and celebrated by the entire community.

This was our least favorite of these books. It is a problematic time to be celebrating monarchy, especially when non-royalty (here, the villagers) are consigned solely to fearing the dragon or cheering Prince and Knight. We don’t really get to know anyone – we don’t even learn Prince’s name! But more importantly, the conflict in this story – Prince’s gayness – is shown as simple and simply solved, which even third-graders will identify as improbable. It’s all very Disney-like, but without challenging any of the foundational beliefs that underlie Disney. The illustrations are Disney-simple too. Perhaps this is a good alternative in a fictional universe filled with Snow Whites and Cinderellas, but we wanted more.

4th grade: Love, Violet by Charlotte, by Sullivan Wild

Violet likes her classmate Mira, who shows every sign of liking her back, but Violet is too shy to tell Mira or even accept Mira’s invitations to play together. To explain her feelings, Violet makes Mira a sparkly, glittery Valentine, but cannot bring herself to deliver it. As in a standard rom-com, Violet is clumsy and tongue-tied, earning the mockery of her classmates – who frankly sound like a bunch of hooligans who should be kept in at recess and required to write “I will behave like a mensch” 500 times. Is it Violet’s hint of mannish dressing that sparks their cruelty? This is never addressed. In the end, Violet and Mira exchanges Valentines and become the best of friends.

It’s a sweet story and the illustrations are dynamic. But again, the problem is simple and the solution equally so. Where are the parents? The teachers? The neighbors? Lord of the Flies it isn’t, but the story conveys a sense of isolation and hopelessness in the way the schoolchildren interact. We want a larger conversation about how to bring all the children along, not just a love/like story.

5th grade: Born Ready: The True Story of a Boy Named Penelope, by Jodie Patterson

In the middle of a busy family, Penelope knows himself to be a boy. In frustration at not being seen, he misbehaves until his mother discovers his feelings. At first she responds insufficiently, telling him that whatever he feels on the inside is fine. Penelope responds that he doesn’t feel like a boy, he is a boy. To her credit, his mother not only validates him, but makes a plan to tell everyone. Penelope: “For the first time, my insides don’t feel like fire. They feel like warm, golden love.” Again, sniffle! Penelope gets the short haircut he wants, and his mother follows through at his birthday party by explaining his new identity to his grandfather from Ghana. Grandpa responds that in his native language, there are no gendered pronouns – “…gender isn’t such a big deal.” Score! However, the story is not over. Older Brother doesn’t believe Penelope can become a boy just by saying so. Mama wisely explains that not everything has to make sense. “This is about love.”

At school, Penelope wears his boy’s uniform and his status is acknowledged by his friends. In an endearing interchange, the principal asks Penelope if he is a boy, and when he confirms the change, the principal says, “Well, Penelope … today you’re my teacher.” The book concludes with Penelope studying karate and owning his power.

This is more like it! Everyone is involved in Penelope’s decision – his immediate family, his grandfather, his schoolmates, his principal. Just as in My Rainbow, this is a portrait of a loving Black family who knows when to stop and listen, and who understands that a decision about identity is not made in isolation, but in community. We loved this book!

CONCLUSION

These seven books all have something to recommend them, although it should be clear from our reviews where our preferences lie. In addition to depictions of LGBTQ individuals and families, most of the books featured excellent representations of varied abled status, race and ethnicity, and age. Most could use improvement in depictions of different body shapes and sizes.

The parents who brought this lawsuit and the justices who found for the parents are, in our opinion, short-sighted at the very least and bigoted and hateful at the worst. In our own schooldays, did we encounter books that did not reflect our family’s religious, moral, and political views? Yes, pretty much everything in the Western canon! However, the point of education is not that students avoid encountering material they disagree with, but that they experience a broad array of materials while developing critical thinking skills so they can evaluate materials in light of their own and their families’ principles, as well as by diverse standards of quality.

We urge you to sample these books! Visit your local library to request the acquisition of these titles if they are not already in the collection, explore interlibrary loan options, and patronize local independently-owned booksellers.

Some people with concerns about the safety or efficacy of vaccines object to the presence of “aborted fetal cells” in vaccines. However easy (and gruesome!) it is to picture a dismembered hand pushing up through a syringe’s liquid, that is not the reality. As the blue-jacketed person in Frame 3 tries to point out, what is in question are cell lines. How are cell lines formed? Scientists use cells taken from

Some people with concerns about the safety or efficacy of vaccines object to the presence of “aborted fetal cells” in vaccines. However easy (and gruesome!) it is to picture a dismembered hand pushing up through a syringe’s liquid, that is not the reality. As the blue-jacketed person in Frame 3 tries to point out, what is in question are cell lines. How are cell lines formed? Scientists use cells taken from  an organism, e.g. kidney cells taken from a dead human embryo, and create a replicating cell line. The original kidney cells eventually die off, just as cells in the body do, and are replaced by genetically identical cells created by standard biological cell division. These cells are then combined with viruses and used to create a vaccine. (For fascinating photos of human embryonic stem cells, see

an organism, e.g. kidney cells taken from a dead human embryo, and create a replicating cell line. The original kidney cells eventually die off, just as cells in the body do, and are replaced by genetically identical cells created by standard biological cell division. These cells are then combined with viruses and used to create a vaccine. (For fascinating photos of human embryonic stem cells, see

Other wrongs, however, remain to be righted: consider the case of Henrietta Lacks. The HeLa cell line was developed from cells taken from the cervical tumor that killed Lacks in 1951. The line has been successfully used for far-reaching discoveries in cancer drugs, space research, and immunology, including in the study of COVID-19 in search for a vaccine. The moral issue arises from the fact that while great good came of the establishment of the line, none of that good was directed specifically toward the Lacks family.

Other wrongs, however, remain to be righted: consider the case of Henrietta Lacks. The HeLa cell line was developed from cells taken from the cervical tumor that killed Lacks in 1951. The line has been successfully used for far-reaching discoveries in cancer drugs, space research, and immunology, including in the study of COVID-19 in search for a vaccine. The moral issue arises from the fact that while great good came of the establishment of the line, none of that good was directed specifically toward the Lacks family.

Finally, regardless of the utility of boycotts and the application of a restorative justice lens to problems of fairness and equality, is there ever a world in which one moral concern can override all others? You might believe, for example, that your cause in life is to

Finally, regardless of the utility of boycotts and the application of a restorative justice lens to problems of fairness and equality, is there ever a world in which one moral concern can override all others? You might believe, for example, that your cause in life is to