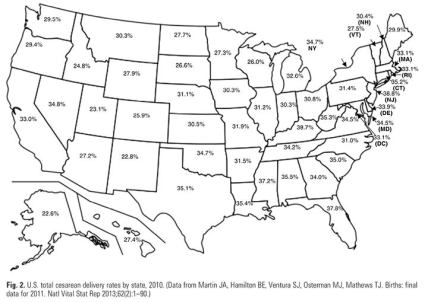

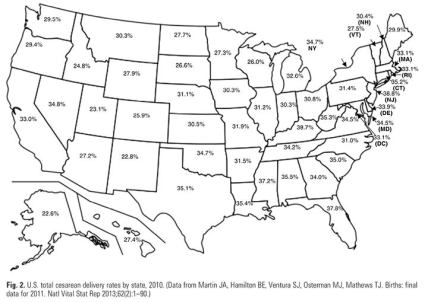

Social networks are abuzz this week following the publication of the article, “Safe Prevention of the Primary Cesarean Delivery,” developed by ACOG (the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists) and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.  The gist of the article is that the U.S. c-section rate, hovering somewhere around 25% of first-time births (and 33% of all births), is too high and measures should be taken to lower it. I couldn’t agree more.

The gist of the article is that the U.S. c-section rate, hovering somewhere around 25% of first-time births (and 33% of all births), is too high and measures should be taken to lower it. I couldn’t agree more.

However, before I fall all over myself congratulating ACOG for its perspicacity, I’d like to call attention to a few truths it has omitted. Commence strategic changes of headgear now!

Late to the party

Late to the party

Members of the overlapping midwifery, physiologic birth, and maternity care reform communities have been warning of the dangers of the rising c-section rate for decades. Because of c-sections’ greater risk of injury to both mother and baby as well as the consequent restrictions on mothers’ fertility, many advocates have emphatically sounded this warning for a long time. I think it’s fair to say that gladness reigns in these communities that ACOG has finally gotten the memo, but many of us would have been happier to see ACOG acknowledge its long delay in coming to these conclusions.

In fact, it would have been reasonable for ACOG to concede that perhaps these communities might be correct in some other stances as well:

- MIdwives are widely acknowledged to be experts in lowering c-section rates, but the word “midwife” appears nowhere in the article. Doulas are mentioned in the context of the benefits of “the presence of continuous one-on-one support during labor and delivery.” However, overlooked is the reason why doulas are necessary: hospitals fail to provide continuous one-on-one support for their pregnant patients. Everyone is familiar with the obstetrician who swoops in at the last moment to catch the baby, but many new parents are not aware that labor and delivery nurses will for the most part be monitoring multiple patients’ fetal monitoring traces from a computer in another room. If ACOG is serious about lowering the c-section rate, it needs to get behind a model of care that can accomplish this. Rather than making patients responsible for providing their own support personnel at added cost, hospitals should step up by establishing and increasing midwifery services and empowering midwives to practice autonomously. As a bonus, hospitals could incorporate doula services.

- Out-of-hospital midwives, particularly when they are direct-entry midwives rather than nurse-midwives, have long faced hostility from ACOG. It’s time for ACOG to recognize that families plan out-of-hospital births for many reasons, and that no amount of censure by obstetricians will change that. If ACOG is serious about lowering the c-section rate and improving the U.S.’s abysmal maternity and infant mortality rate, it should be falling over itself to learn from these midwives who are experts in protecting physiologic birth. It would also be a show of good faith if ACOG recommended protocols for hospital for receiving appropriate home birth transfers, as home birth is made safer if smooth transfers are a given. Finally, ACOG might consider throwing its political might behind state legislative measures to license direct-entry midwives and to permit nurse-midwives to practice autonomously to their full scope of practice.

- While the article addressed limits on interventions such as inductions that are known to increase the number of c-sections, it left out others of the other widely acknowledged healthy birth practices, including encouraging patients in labor to move around and to avoid giving birth on their backs, and to refuse unnecessary interventions shown to increase c-sections, such as continuous electronic fetal monitoring.

Overall, I would remind ACOG that its members are experts in performing c-sections – and thank goodness, because this surgery can be life-saving. But to reduce the number of c-sections, ACOG would do well to look elsewhere for guidance.

Causation, correlation, and stigma

Causation, correlation, and stigma

It’s not only Weight Watchers, the First Lady, supermarket tabloids, and everyone’s family members who shame people for their size; medicine jumped on this bandwagon a long time ago. It is rare for a research study examining some aspect of pregnancy or childbirth to avoid blaming fat women for increased risk. The ACOG article doesn’t disappoint:

A large proportion of women in the United States gain more weight during pregnancy than is recommended by the Institute of Medicine (IOM). Observational evidence suggests that women who gain more weight than recommended by the IOM guidelines have an increased risk of cesarean delivery and other adverse outcomes. In a recent Committee Opinion, the College recommends that it is “important to discuss appropriate weight gain, diet, and exercise at the initial visit and periodically throughout the pregnancy.” Although pregnancy weight-management interventions continue to be developed and have yet to translate into reduced rates of cesarean delivery or morbidity, the available observational data support that women should be counseled about the IOM maternal weight guidelines in an attempt to avoid excessive weight gain. (Citations removed)

While to the uninitiated this paragraph might seem eminently sensible, I invite you to consider the following thoughts:

- The correlational evidence between weight gain and increase in c-sections is somewhat less than solid, by ACOG’s own admission. Even if the correlation were solid, it doesn’t mean that managing weight gain would resolve the problem – after all, the weight gain and adverse outcomes might both be caused by some third factor. Finally, even if causation were shown, there are vast amounts of evidence to show that in general, trying to control weight through restrictive eating and increased exercise is a losing game. In pregnancy, restricting intake may well have harmful effects on the child. One of the best sources for information on these matters is Pamela Vireday’s website, The Well-Rounded Mama.

- Vireday also points out that adverse pregnancy outcomes for fat women can at least partially be attributed to weight bias-influenced pregnancy management practices. In addition, the effects of stigma as physiological mechanisms are beginning to be known; these effects might also account for some outcome disparities. Rather than demanding that pregnant patients their weight, providers might instead refrain from practices rooted in bias that increase stigma.

- Finally, because poor nutrition and too much or too little exercise can be bad for people of all shapes and sizes, it would be more reasonable – and easier! – for practitioners to recommend good nutrition and appropriate exercise to all their patients rather than to target fat patients with weight control advice. This approach is in fact a feature of midwifery-led care and of the Health at Every Size philosophy.

However inured we have become to messages positioning fat as the the next Great Terror, I suggests we think critically about fairness, practicality, and evidence when making recommendations about what size or shape pregnant people should be.

Let’s blame all the lawyers

Let’s blame all the lawyers

Physician anxiety over potential medical malpractice liability is a frequent topic when practice reforms are under discussion, particularly in the high-stake field of obstetrics. The typical solution proposed is tort reform – specifically, legislature-imposed caps on damage awards to injured parties. ACOG falls right into step:

A necessary component of culture change will be tort reform because the practice environment is extremely vulnerable to external medico-legal pressures. Studies have demonstrated associations between cesarean delivery rates and malpractice premiums and state-level tort regulations, such as caps on damages. A broad range of evidence-based approaches will be necessary––including changes in individual clinician practice patterns, development of clinical management guidelines from a broad range of organizations, implementation of systemic approaches at the organizational level and regional level, and tort reform––to ensure that unnecessary cesarean deliveries are reduced. (Citations removed and emphasis added)

Caps on damages, currently in place in a majority of states, can certainly lower the costs negligent physicians pay in damage awards and thus lower anxiety about liability, which in turn may lead to fewer c-sections. However, this strategy is akin to alleviating a family’s anxiety about its grocery bills by having it cut out breakfast and dinner each day: it solves one problem while creating a much more serious one.

The civil justice (“tort”) system enables individuals to obtain redress for civil wrongs without deploying government to do so; once a state government has established the necessary courts and basic rules of the game, private entities move the action along. Accordingly, the civil justice system is one of the few arenas in which individuals have the power to challenge negligent behavior of large, influential entities. In the realm of medical malpractice litigation, this capacity is further facilitated by the contingency fee arrangement that allows litigants to engage an attorney without paying a retainer fee. Attorneys front the costs of cases and receive payment only if the case is successful.

To limit the amount of damages awarded by juries is to undercut the redress that injured individuals can receive. If medicine wishes to avoid malpractice liability, numerous solutions are available:

- Refrain from committing malpractice!

- Eliminate the need for compensation. If families with babies injured at birth could be sure that the care required for the rest of the children’s lives would be available and accessible to them, one economic motivation for bringing suit would be removed. The considerable power of the medical lobby should be brought to bear on strengthening and broadening collective systems that compensate victims of illness, injury, and disability, such as Medicare and Social Security.

- An approach pioneered by the University of Michigan demonstrates that liability after adverse events can be reduced when medical institutions provide 1. open communication and record sharing with patients, 2. early offers to settle when the institution is at fault and corresponding refusal to settle when not at fault, and 3. (if the institution is at fault) systemic changes, so the error is not repeated.

The three points above have been made before, and by wiser heads than mine. Rarely discussed, however, is the relative powerlessness of mothers to use the tort system to discourage non-medically-indicated c-sections. As the c-section has grown to an ever-greater proportion of American births, its potential harms have been increasingly played down, particularly those harms that are not apparent until subsequent pregnancies. As a result, projected damage awards are insufficient to induce plaintiffs’ attorneys to mount such cases and tort law thus fails to fulfill one of its functions of a feedback system to deter unsafe medical practices.

In “Distorted and Diminished Tort Claims for Women,” Jamie Abrams contends that tort law has come to privilege the claims of injured babies over those of their mothers in a way that “diminish[es] the birthing woman as a patient and a putative plaintiff.” She connects this primacy of the fetus as patient and plaintiff with the decline of the mother’s role as decision-maker for herself and the fetus. Among her recommendations to reverse this trend, Abrams suggests that “more pursuits of maternal harms claims are necessary. Even if the ultimate damage verdicts are nominal, the pursuit of damages will push courts to consider more carefully the harms to mothers and perhaps influence the standard of care.” If such actions could normalize for attorneys, judges, and juries the idea that unwanted and non-medically-indicated c-sections constitute harm to pregnant patients, just as the ACOG article finally admits, this might re-establish a remedy for patients who have suffered these harms. Furthermore, the tort system’s feedback function would then re-emerge to provide a counterweight to physicians’ traditional concerns that not performing c-sections exposes them to liability.

* * * * *

In summary, I congratulate ACOG on joining the party, however late, and urge it to mingle with all the guests, giving credit where credit is due. If ACOG can acknowledge the knowledge and experience of pregnant people, midwives, and yes, even lawyers, we might all join together to reverse the mounting c-section trend and make a safer world for parents and babies – and a less anxious one for physicians as well.

In summary, I congratulate ACOG on joining the party, however late, and urge it to mingle with all the guests, giving credit where credit is due. If ACOG can acknowledge the knowledge and experience of pregnant people, midwives, and yes, even lawyers, we might all join together to reverse the mounting c-section trend and make a safer world for parents and babies – and a less anxious one for physicians as well.

President Obama supports equal pay for equal work, and I’m glad of it. But that is hardly a new proposition.

President Obama supports equal pay for equal work, and I’m glad of it. But that is hardly a new proposition.