Forty Years in the Wilderness

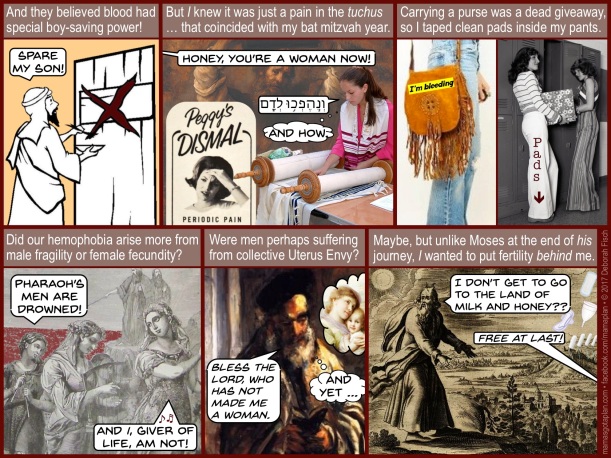

Forty years is a long time to seek a home. With Passover approaching and U.S. politics running wild, it’s tempting to view the biblical journey through the desert as a metaphor for current-day immigration policy – or global warming, or the nature of leadership. However, your cartoonist feels that a woman’s 40-year fertile capacity (more or less) lends itself nicely to a comparison with the journey to the Holy Land. So – let the menstruation train leave the station!

This is your life!

In the late 1970s, girls were less well informed on matters of reproductive health. Some of us were lucky enough to have mothers who gave us copies of Our Bodies, Ourselves, the classic women’s health book. It contained an

In the late 1970s, girls were less well informed on matters of reproductive health. Some of us were lucky enough to have mothers who gave us copies of Our Bodies, Ourselves, the classic women’s health book. It contained an  informative diagram of reproductive anatomy, with some helpful words about menstruation:

informative diagram of reproductive anatomy, with some helpful words about menstruation:

Starting to menstruate will always be different for each person – welcome to some, just the beginning of inconvenience for others.

Liberal mothers also gave their daughters copies of Judy Blume’s books; Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret was the Platonic ideal of menstrual fiction.

Nevertheless, the predominant source of information for pre-internet and pre-video-era girls searching for more relevant information than we received in our sixth-grade Kotex-sponsored filmstrips was, of course, movies and TV. In Carrie, Sissy Spacek’s wonderful and terrifying performance of menarche-triggered telekinesis did not convince us of our ability to cause knives to fly across the room (more’s the pity), but it did present some – wholly incorrect – estimations about the amount of blood involved in a menstrual cycle. Fast Times at Ridgemont High wasn’t specifically about menstruation, but it was about adolescent awakening. We couldn’t resist the photo of Phoebe Cates and Jennifer Jason Leigh discussing sex while slicing a sausage.

Nevertheless, the predominant source of information for pre-internet and pre-video-era girls searching for more relevant information than we received in our sixth-grade Kotex-sponsored filmstrips was, of course, movies and TV. In Carrie, Sissy Spacek’s wonderful and terrifying performance of menarche-triggered telekinesis did not convince us of our ability to cause knives to fly across the room (more’s the pity), but it did present some – wholly incorrect – estimations about the amount of blood involved in a menstrual cycle. Fast Times at Ridgemont High wasn’t specifically about menstruation, but it was about adolescent awakening. We couldn’t resist the photo of Phoebe Cates and Jennifer Jason Leigh discussing sex while slicing a sausage.

The 1972 episode of Norman Lear’s Maude, in which the title character considers – and obtains – an abortion, was a first in TV history. Yet to girls five years later, the shock was that Maude could get pregnant at all. Did people that old still have sex? Even in our surprise, however, we never considered what this might mean for our menstrual selves. Had we understood the implications – and had Costco existed at that point – we might have stocked up on truckloads of feminine hygiene products.

The 1972 episode of Norman Lear’s Maude, in which the title character considers – and obtains – an abortion, was a first in TV history. Yet to girls five years later, the shock was that Maude could get pregnant at all. Did people that old still have sex? Even in our surprise, however, we never considered what this might mean for our menstrual selves. Had we understood the implications – and had Costco existed at that point – we might have stocked up on truckloads of feminine hygiene products.

In that context, menopause does seem a lot like the Promised Land.

The Red Stuff

The Passover story is full of blood. We’ve taken certain liberties with the text, but the raw material, if you’ll excuse the phrase, was already there. The first of the Ten Plagues turned the waters of the Nile into blood. The final plague slew the first-born sons of all those who had not painted their doors with blood from the Passover sacrifice. This was hardly menstrual blood (although think of the lambs they might have saved!) – but still, as far as symbols go, blood is blood.

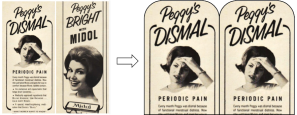

Returning to a more personal history, we repurposed this 1950s advertisement for Midol into a shape

Returning to a more personal history, we repurposed this 1950s advertisement for Midol into a shape suggestive of the stone tablets Moses is about to smash in the background.

suggestive of the stone tablets Moses is about to smash in the background.

The bat mitzvah girl shown is perhaps less than thrilled with her new-found womanhood; she seems to be reading the phrase from Exodus 7:17, “and it will turn to blood,” with something of an attitude.

Her attitude might well derive from the difficulties girls faced – at least in the time and circumstances this cartoon presents – in adapting their lives to a menstrual cycle.

But in the end, what is our cultural aversion to blood all about? What makes blood so scary, or at least so significant? One might argue that most people who aren’t surgeons or phlebotomists are unaccustomed to encountering blood outside the body, and that we therefore find something transgressive in its appearance. But wait! Who sees blood every month! And what does it mean?

Miriam rejoices after the Israelites have crossed the Red Sea. (We know it’s really the Reed Sea, but humor us, please.) Perhaps she is celebrating more than a narrow escape: that is, her own superiority as a woman to the men who perished. They can only fight and die, but she can create new people. How like a deity! In fact, her exclamation is ambiguous: is she apostrophizing the Giver of Life or does she consider herself the giver of life? Of course, all of this is your cartoonist’s invention, as Exodus does not feature Miriam celebrating her capacity for procreation.

Miriam rejoices after the Israelites have crossed the Red Sea. (We know it’s really the Reed Sea, but humor us, please.) Perhaps she is celebrating more than a narrow escape: that is, her own superiority as a woman to the men who perished. They can only fight and die, but she can create new people. How like a deity! In fact, her exclamation is ambiguous: is she apostrophizing the Giver of Life or does she consider herself the giver of life? Of course, all of this is your cartoonist’s invention, as Exodus does not feature Miriam celebrating her capacity for procreation.

A traditional morning blessing said by Jewish men thanks the Almighty for not creating them as

women. Could it be they protest too much? This prayerful man is having second thoughts, remembering the mother and child of his youth. When we penned the words “Uterus Envy,” we had no idea that this concept existed outside our cartoon. It turns out that neo-Freudian psychiatrist Karen Horney (1885–1952) got there first, creating the concept of Womb Envy.

women. Could it be they protest too much? This prayerful man is having second thoughts, remembering the mother and child of his youth. When we penned the words “Uterus Envy,” we had no idea that this concept existed outside our cartoon. It turns out that neo-Freudian psychiatrist Karen Horney (1885–1952) got there first, creating the concept of Womb Envy.

What does Womb Envy mean to a woman who has had 40 years of a hard-working uterus? Not much. The Promised Land may represent the delights of fertility unachievable by Moses, while simultaneously symbolizing freedom from fertility to women who have been there and done that.

Image Credits

The title frame features the painting, Moses leading the Israelites out of Egypt, by József Molnár, 1861. This work is in the public domain.

Frame 5: Moses Viewing the Promised Land, by Frederic Edwin Church, 1846. This work is in the public domain.

Frame 7: The Story of Passover by Marking the Israelites Door Coloring Page is shared under a Creative Commons license.

Frame 8: Moses Smashing the Tablets of the Law, by Rembradt, 1659. This work is in the public domain. The photo, A Conservative bat mitzvah in Israel, is shared here under a Creative Commons license.

Frame 10: Miriam and the Israelites Rejoicing, an illustration from the Holman Bible, 1890. This work is in the public domain.

Frame 11: A Jewish Man in His Prayer Shawl, by Lesser Ury, 1931. This work is in the public domain.

Motherly Love, by Gabriel Cornelius Ritter von Max (1840-1915). This work is in the public domain.

Frame 12: Moses Views the Promised Land, an engraving by Gerard Jollain from the 1670 La Saincte Bible. This work is in the public domain.