Another cartoon in the Ask the Right Question series created for Friends of Michigan Midwives in early 2016!

[Updated July 16, 2016, to add copyright designation.]

via Ask the Right Question: The C-Section Question — Friends of Michigan Midwives

by Mama

Another cartoon in the Ask the Right Question series created for Friends of Michigan Midwives in early 2016!

[Updated July 16, 2016, to add copyright designation.]

via Ask the Right Question: The C-Section Question — Friends of Michigan Midwives

by Mama

Another cartoon in the Ask the Right Question series created for Friends of Michigan Midwives in early 2016.

[Updated July 16, 2016, to add copyright designation.] [Updated November 16, 2016, to fix broken image.]

via Ask the Right Question: The Access Question — Friends of Michigan Midwives

by Mama

We begin here reblogging a number of cartoons we created for other organizations.

This is the first cartoon in the Ask the Right Question series created for Friends of Michigan Midwives in early 2016.

[Updated July 16, 2016, to add copyright designation.]

via Ask the Right Question: The Safety Question — Friends of Michigan Midwives

by Mama

This cartoon grew out of the study of different constitutional theories of abortion rights, some better known than others. The First and Second Amendments of the Constitution have infiltrated the popular imagination, but the Third -? What is the Third Amendment, anyway?

Frame 1. The soldier in the title frame is General John Burgoyne, as shown in his portrait by Sir Joshua Reynolds, c. 1760.

Frame 2. Justice William O. Douglas first articulated the Privacy framework in the case of Griswold v. Connecticut (381 U.S. 479 (1965)), which concerned not abortion rights, but the right of married couples to use contraception. As Privacy is not a right specifically named in the Constitution, Douglas introduced the concept of a penumbra, a shadow or cloud emanating from the Bill of Rights, chiefly the First Amendment. Privacy was defined as preventing the government from interfering with marital privacy. This protected area was later expanded to rights to contraception for unmarried people, and then to abortion rights (see Roe v. Wade, 410 U.S. 113 (1973).

Frame 3. Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg believed that abortion rights were better protected by the Fourteenth Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause:

“… legal challenges to undue restrictions on abortion procedures do not seek to vindicate some generalized notion of privacy; rather, they center on a woman’s autonomy to determine her life’s course, and thus to enjoy equal citizenship stature.”

– Gonzales v. Carthart, 550 U.S. 124 (2007), dissent

Ginsburg’s critique of Roe‘s constitutional basis is described in greater detail in this article. Neil S. Siegel and Reva B. Siegel, in their 2013 journal article, “Equality Arguments for Abortion Rights,” further explore the Equal Protection argument by quoting Justice Blackmun’s dissent in Planned Parenthood v. Casey. Blackmun asserts that the Court’s assumption that women “can simply be forced to accept the ‘natural’ status and incidents of motherhood—appears to rest upon a conception of women’s role that has triggered the protection of the Equal Protection Clause.”

Frame 4. According to the History Channel, the photo of African-Americans in the cotton fields represents a “slave family standing next to baskets of recently-picked cotton near Savannah, Georgia in the 1860s.” The realities of slavery with respect to women’s reproduction has been ably addressed by Dorothy Roberts and Rickie Solinger, who discuss both the coercive nature of these women’s pregnancies as well as their subjugation to the role of producers of future slaves.

The connection to abortion rights is the Thirteenth Amendment, which forbids slavery and involuntary servitude. Legal scholar Andrew Koppelman, in his 2012 article, “Originalism, Abortion, and the Thirteenth Amendment,” draws an analogy between the forced labor of slaves, including their forced reproduction, and the forced labor of women compelled by abortion bans to carry their pregnancy to term. Of course, Koppelman is not claiming that absence of abortion access is equivalent in severity to the past system of slavery in this country, only that both issues can be seen as a violation of the Thirteenth Amendment.

Frame 5. The crowd at the 2004 March for Women’s Lives seems puzzled by the Third Amendment. The photo of the march by Bubamara, shared under a Creative Commons license, is augmented by an airplane towing a “Keep Abortion Legal” sign.

Frame 6. At last! All is explained! The Third Amendment forbids the forcible housing of military personnel in citizens’ homes. Its incorporation in the Bill of Rights was a reaction by the Founders to that very practice carried out by the British during the Revolutionary War. The home pictured here is the Brewster House of Setauket, New York, built in 1665. The photo is by Iracaz, shared under a Creative Commons license. The reluctant B&B host is taken from a work housed in the New York Public Library. She is Elizabeth Zane, whose exploits are detailed here; apparently, she was the inspiration for Zane Grey’s Betty Zane (1903), the first volume of his Ohio River Trilogy.

Frame 7. The Guttmacher Institute, one of the prime sources of U.S. abortion data, lists state abortion restrictions enacted during the last several years. The old woman in the shoe, it is surmised here, has so many children that she doesn’t know what to do because of these abortion restrictions. She accuses the state of forcibly housing a fetus in her uterus.

Frame 8. Prepare for a romp through property law, Dear Reader! (Remember, don’t go to law school.) We apply this question: when can someone else be in your home? In this frame, the fetus is compared to a guest who has been invited but is now being asked to leave – as is acceptable at common law, under which tenants or guests of property owners possess relatively few rights. The scene shown, for those who came of age after reruns of The Jeffersons ceased, is of Mr. Jefferson ejecting Mr. Bentley. The dialog, however, is taken not from The Jeffersons, but from The Spellbinders Collection. Our thanks to Ed G. for suggesting this source.

Frame 9. On the other hand, perhaps the fetus is more like a tenant delinquent in rent payments and now facing eviction, as shown in this 1892 painting, Evicted, by Danish artist Erik Henningsen. This image is in the public domain. This comparison highlights the uncompensated nature of women’s labor: the fetus, after all, gives no consideration in exchange for housing – and neither does the state that imposes abortion restrictions.

Frame 10. We move on to trespassing. Harrison Ford, as President James Marshall, spends most of Air Force One (1997) playing hide-and-seek with a deadly group of planenappers. When the president finally gets Gary Oldham (“Ivan”) in his clutches, Ivan finds himself violently pushed off the plane. We show the classic line in a still from another scene (in which the president growls, “Leave my family alone!”). The true scene of Ivan’s end is here. It is worth mentioning that property owners are discouraged from using self-help to eject trespassers; since the president had no sheriff accessible, he can probably be forgiven for taking matters into his own hands.

Whether the fetus is trespassing on the pregnant person is an interesting philosophical question. However, given that almost half of all U.S. pregnancies are unplanned, it is fair to say that in many cases the fetus is present against the pregnant person’s wishes.

Frame 11. Even a person who comes on the land without the owner’s permission may gain some property rights. A prescriptive easement is granted when a person takes adverse possession of the land: their use of the land is open, notorious, and hostile. That is, they use the land openly and against the owner’s wishes, continuously over the course of a statutory period defined by the state. At the end of this period, they are granted an easement to be on the land.

In Michigan, the statutory period is fifteen years. Therefore, we show a fifteen-year-old fetus establishing a Disco in Utero. Even if she is there without her mother’s permission, may she invoke the law in continuing to occupy the space, operate strobe lights and loud music, and dance all night?

Confirmation of the Michigan fifteen-year statutory period led to immediate thoughts of a prenatal quinceañera celebration. Alas, there is not room here to explore this idea; the concept will have to be set aside for another cartoon. Forewarned!

Please note that this image is the only instance in this cartoon of a visibly pregnant person. That is because 65% of abortions in the U.S. are carried out by eight weeks’ gestation, before most pregnancies have begun to show at all. In fact, 91% of all abortions are carried out by thirteen weeks, still very early in a typical 40-week pregnancy. We felt that a fifteen-year gestation, on the other hand, really demanded a visibly pregnant person.

Frame 12. The final frame shows a 1787 painting of the Hartley family, by Henry Benbridge. We discovered this painting on the blog 18C American Women, maintained by art historian Barbara Wells Sarudy; we later tracked it down to the collection of the Princeton University Art Museum.

The ladies of Family Hartley are declaring their autonomy and personhood as an explanation of why an analogy of the fetus to an occupier of maternal land must ultimately fail. To separate pregnant person and fetus as conflicting entities – occupier and occupied – is tempting but unsound. As explained by the authors of Laboring On: Birth in Transition in the United States, mother and fetus constitute a bonded dyad.

A fetus is neither property nor a legal person, but a potential person. Women are not houses, airplanes, or discos. The fetus is not their possession, but part of them. The reason that pregnant people are the best decision-makers about abortion – or childbirth, for that matter – is that they are the experts. They hold close to their hearts the interests of their families, present and future, their own lives, and their many other responsibilities.

Your cartoonist expresses gratitude to SMV for inspiring this cartoon through his persistent complaints of the sad neglect of the Third Amendment in both U.S. jurisprudence and high school government classes.

[Updated Oct. 22, 2016, for some minor grammar and punctuation fixes. Updated Oct. 23, 2016, to fix factual error about Griswold.]

[Updated Oct. 11, 2017, to fix capitalization errors and the spelling of Gary Oldham’s name. In addition, we deleted a few sentences at the end of the post that we had unconsciously lifted from the end of a Margaret Drabble novel!]

[Updated July 25, 2021, to fix style and punctuation issues.]

by Mama

Publicity for the upcoming annual conference of the Midwives Alliance of North America, combined with this summer’s Republican and Democratic national conventions, were the twin inspirations for this cartoon. It seems unlikely that we will elect a midwife-in-chief anytime soon, but cherishing midwives’ skills and experience under the cover of political maneuvering seems like an end in itself.

Frame 1. The background photo is from one of this summer’s conventions. Does it matter which? The MNC logo is based on a graphic by Sam Taeguk, shared under a Creative Commons license.

Frame 2. Every gathering needs a quilt exhibit! This quilt is intended to convey – by the variety of fabrics in the baby blocks – the diversity of North American midwifery. Every midwife has been caught out at least once wearing good clothes when the urgent summons to a birth arrives. What to do with those stubborn stains? When Spray N Wash fails, cut up that fabric for a quilt! Many thanks to Kathy Peters for her quilt design skills. The person gazing at the quilt is taken from a photo by Phil Roeder, shared under a Creative Commons license.

Frame 3. The photo by Pete Souza shows a 2009 meeting of President Obama’s cabinet, shared under a Creative Commons license. We’ve taken the liberty of cropping out the President, but perceptive readers will recognize individual cabinet members.

Frame 4. This frame shows the White House Situation Room, as portrayed in The West Wing.

Frame 5. This song, published in 1980 by Molly Scott of Sumitra, is sung here in the U.S. House of Representatives.

Frame 6. Anyone with knowledge of the midwifery model of care will recognize the original context for the words MANA president Marinah Farrell is speaking to Vladimir Putin against the background of the Oval Office:

Laboring person: I can't do it!!! Midwife: You're doing it!

The Midwifey Face is an invention of your cartoonist, who theorizes that midwives are endowed with special facial features or expressions that allow them to persuade anyone to do anything, no matter how difficult.

by Mama

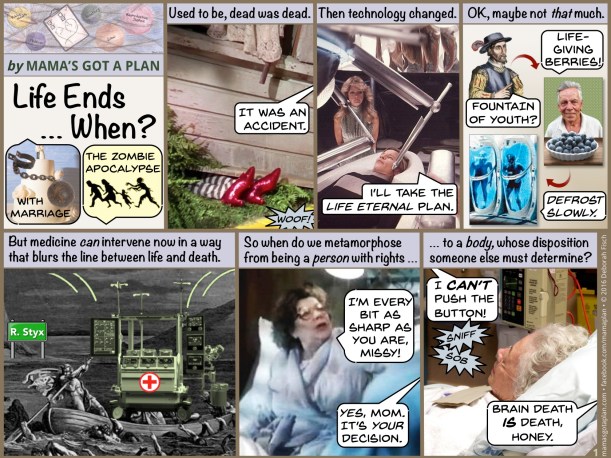

Once the cartoon Life begins … when? was posted, it seemed only natural to start work on the other end of the mortal coil – the shuffling-off end. The content of this cartoon is a little looser, compared with Life begins. After all, while we know more or less what happens when someone is born, death remains the big mystery.

Therefore, although this cartoon begins with an attempt to establish the elusive line between life and death, it goes on to comment on the nature of state law on the matter, the difficult cases of dead-but-not-really-dead people, the impact of pregnancy on dying, and a look at what happens when patients want to die.

In closing, the cartoon shows the aftermath of a tragic group of deaths we experienced as a nation. How are we to be healed?

Frames 2 and 3. Hollywood lives in these frames! Or perhaps dies, as did the Bad Witch in the Wizard of Oz. The scary-looking machine with Farrah Fawcett in the background is from Logan’s Run (1976). We must confess that in the film it was actually a machine that refashioned people’s faces. We refashioned it for our own purposes to be a life-extending machine.

Frame 4. The gentleman contemplating the blueberries is from a photograph by Oliver Delgado.

Frame 5. The illustration is Crossing the Styx, by Paul Gustave Doré (1861). The device shown dropping onto Charon’s boat is a heart-lung machine.

Frame 6. Mrs. Huffnagl was a recurring character in the 1980s medical drama St. Elsewhere. She is included here because of her iconic status as a Problem Patient, but also as a nod to our nostalgia for the television series of our youth.

Frame 7. The photo of the elderly patient is by melodi2. The point here is that a body kept alive by artificial respiration devices or other medical aids is nevertheless considered dead in the total absence of brain activity.

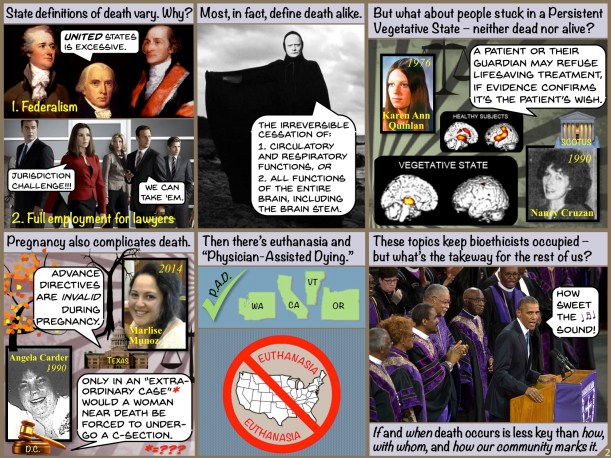

Frame 8. Federalism, the idea that multiple states are governed by a central entity yet still retain significant powers of governance, is a function of a very American history. Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay may not have spoken the exact words shown emerging from Madison’s mouth, but they certainly believed in curtailing the powers of the federal government – thus enabling individual states to deviate from any one definition of death.

Multiple systems of law leads to both jurisdictional challenges and conflicts of laws. We admit to including these two images mostly because it was good fun to put words in the mouths of the Federalists and the cast of The Good Wife all at once.

Frame 9. The Uniform Determination of Death Act is model legislation created in 1981 and subsequently adopted by all U.S. states. Some states attached additional language; this accounts for the variation in state law.

Speaking the standard definition in this frame is – who else? – Death, from Ingmar Bergman’s classic film, The Seventh Seal (1957), as portrayed by Bengt Ekerot.

Frame 10. The images of brains in both healthy and vegetative states are taken from a larger graphic produced by the Université de Liège.

Two court cases defined the early days when law was forced by medical advances to consider the rights of patients who were not dead, as they retained some amount of brain activity, if only in the brain stem, but were also not conscious and unlikely to regain consciousness. In Re Quinlan (NJ 1976) concerned a 21-year-old who entered into a coma and later a persistent vegetative state (PVS) following her ingestion of alcohol combined with other medications. Her parents were finally permitted to withdraw life-saving treatment (here, a respirator), under their right to privacy, as extended to the right to refuse medical treatment.

Cruzan v. Director, Mo. Dept. of Health (US 1990), was the more significant case, with an opinion issued by the U.S. Supreme Court. Cruzan, like Quinlan, arrived at a persistent vegetative state, in her case as the result of a car accident. The Supreme Court found a fundamental right to refuse treatment under the “clear and convincing” evidentiary standard that evaluates the wishes of incompetent patients. Specifically, Quinlan’s nutrition and hydration devices were permitted to be terminated because a friend was able to show that Quinlan had earlier declared that under circumstances that encompassed the PVS, she would not wish to live.

The shift of the jurisprudence from determining when death occurs to when death is permitted to occur leads us to consider other complications the boundaries between life and death: babies.

Frame 11. The Ur-case of what may or may not be done to a pregnant woman on the brink of death is In re A.C. (573 A. 2d 1235, D.C. App. 1990). Angela Carder, a terminal cancer patient in the last days of life, was subjected to an unconsented-to cesarean section, authorized by a court order obtained by a hospital physician who believed the institution bore an obligation to save Carder’s 26-week fetus. Both Carder and the fetus died following the surgery; the appeals court found that the court order had been improperly granted because there had been no formal attempt to determine her competency before overruling her wishes.

It is widely felt that the broader implications of the case assure that pregnant women cannot be forced to undergo procedures for the sake of the fetus. However, in practice, the opinion does not quite reach this level of authority, for several reasons. First, the opinion is from the equivalent of a state court, and so formally controls the disposition of this issue only in the District of Columbia. Second, the ruling depends on a competency determination, and so never reaches the question of what to do when a pregnant person is competent and is forced to undergo a procedure. Finally, the opinion cites prominently an earlier Georgia opinion that distinguished its forcible c-section as one that was carried out for the benefit of both a mother and her fetus. It does not require great imagination to understand how many instances of forced c-sections could be construed in this manner. However, A.C. does seem to provide some protection against the hastening of a dying mother’s death for the sake of the fetus’s welfare. We have written more about the issue of unconsented-to c-sections here.

More to the point, perhaps, is the case of Marlise Munoz, a Texas paramedic who was found by her husband, also a paramedic, after she suffered a pulmonary embolism. At the time she was pronounced dead, she was pregnant with a 14-week fetus. As a result, her body was kept functioning in opposition her earlier-expressed wishes and those of her family. The family was ultimately able to disconnect Munoz’s body from medical devices after proof was obtained that the fetus would not survive to viability. Like Texas, the majority of states invalidate advanced directives during pregnancy.

Frame 12. Possibly an even more divisive situation is that of the patient who decides to die. As with giving birth, patients may die whenever they wish to, but they are severely limited in who may legally assist them. Euthanasia, defined as a medical provider administering the means of death to a patient, is forbidden in all fifty states, with exceptions for capital punishment in those states that continue to pass such sentences under state law. “Physician-Assisted Dying” (PAD), on the other hand, is defined as a physician providing the means of death to a patient, including by prescription. The patient is then responsible for administering the medication. Only four states permit PAD. One can argue whether people are indeed free to die if they do not, for example, have the use of their hands, or are unable to swallow. That, however, is a very large and complicated topic, far beyond our scope here. Readers wishing to explore it from a perspective that is at once both comic and horrifying, may enjoy Ian McEwan’s 1999 novel, Amsterdam.

Frame 13. Emerging from the thicket of decisions about when people are dead and what the law believes their rights to be, we come to the question of what really matters for most of us in the presence of death. The answer seems to be process. President Obama is shown in this photo by Lawrence Jackson singing “Amazing Grace” at the funeral of the Reverend Clementa Pinckney, one of the victims of the terrible racially-motivated killings at Mother Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal church in Charleston, South Carolina in 2015. The importance of the community’s reverence for the dead and the observance of rituals particular to that community cannot be overstated. We are tremendously grateful to retired home birth midwife Merilynne Rush, who now works on Death Cafes and home funeral care, for consulting with us on this cartoon and helping us to take in this reality.

Many have been known to ask when life begins, in an attempt to establish boundaries for policy issues connected with female reproduction. We wonder whether that question can possibly give a sufficiently definitive answer to guide us in our quest. If it can’t, we might do better to turn to some other defining scheme – such as the wishes of the mother whose body stands between the world and the baby-to-be.

The spherical building welcoming the sperm is in real life the “Kugelmugel,” a micronation located in Vienna.

The clock radio photo, by Chrissy Wainwright, is titled “It’s Too Early!” It is shared here under a Creative Commons license.

The dugout photo demonstrating implantation is by Christian Bickel, described as “Speisekammern in Keldur” (food chamber – probably storage – in Keldur). It shows an example of an Icelandic turf house.

The photo representing red menstrual waters is by Derek Harper, entitled “Red Sea at Babbacombe.” It is shared here under a Creative Commons license.

The pink building shown in Frame 4 is, of course, the Jackson Women’s Health Organization, in Jackson Mississippi, where the awe-inspiring Dr. Willie Parker practices.

The court cases mentioned on Page 2 are quite well-known and easily found online, should you wish to read the opinions. No cases are mentioned for the criminalization of pregnancy (Frame 4), but a visit to National Advocates for Pregnant Women will tell you all you need to know.

The adorable baby with doting mama were captured by Bonnie U. Gruenberg. The photo is shared here under a Creative Commons license.

The orange chair and other clipart were taken from cliparts.co.

The statue shown in Frame 4 on Page 2 is of unknown origin, although several photos of it can be found online, including here, where it is suggested the statue depicts (biblical) Rachel weeping for her children.

The police officer and the representation of the Big Bang are shared here under a Creative Commons license.

Updated November 2, 2017, to fix a typographical error.

by Mama

This cartoon grew out of our astonishment that, particularly in the context of childbirth, U.S. law seemed to most strongly approve the right to refuse care when the refusal was based on irrational grounds. Evidence-based refusals both in law and in fact seemed to meet with much stronger resistance.

The right to refuse care is itself based on the overarching ethical principle of informed consent. While common understanding of informed consent is that a patient has signed a consent form that allows a provider to continue with a suggested treatment or procedure, in reality informed consent is – or should be – a repeated process, in which the following actions take place:

Although informed consent requirements are now incorporated into patients’ rights acts in some states, informed consent doctrine has traditionally evolved as interpreted through a line of court cases, as shown in this cartoon in dark red text.

Some provisions in state statute allow providers to refuse to offer care and require that parents accept care for their minor children.

Frame 1. The building in the background is, of course, the U.S. Supreme Court building.

Frame 2. Count Dracula is refusing a transfusion because he is a practicing Jehovah’s Witness, as signified by the copy of The Watchtower tucked under his arm.

Frame 3. Parents do have to put their foot down on serious matters like broken legs and Sunday School attendance. Parents are empowered by law to make medical decisions for their minor children. Children cannot give informed consent, although they are – ideally – consulted to see whether they assent to care. Little Jimmy apparently does not.

Frame 4. Thanksgiving dinner, when the family is all present and dismantling a large bird, seems the ideal time to talk about donating body parts. It’s either that or politics, right?

Frame 5. The nurse in this illustration is invoking a conscience clause right to refuse to assist with an abortion. If the refusal seems sudden, that is because state law does not require providers to register their refusal at any given time – or indeed, forbid them from changing their stance at any time.

Frame 6. Tamesha Means’s less than forthright provider (see Tamesha Means v. United State Conference of Catholic Bishops, above) did not inform her that she was suffering from an infection that could ultimately prove life-threatening. Means was fortunate not to be permanently injured, unlike a case in Ireland that ended tragically. See the story of Savita Halappanavar.

Frame 7. Many providers believe that a signed informed consent form of the kind that is often required when a patient is admitted to a maternity care unit constitutes a contract that cannot be changed. Nothing could be farther from the truth. Consent can be revoked vocally at any time.

Frame 8. The topic of who decides for the fetus is a rich one – and much too complex to include in this cartoon. Move along now!

Frame 9. Medical malpractice liability is often held up as an excuse for ignoring informed consent requirements – or as an opportunity to blame lawyers. (Health care providers tend to forget that lawyers defend them too!) This frame seeks to make the point that there is no corresponding liability avoidance right for the provider that would trump the patient’s right to refuse care.

Frame 10. Continuous electronic fetal monitoring (EFM) for all pregnancies is the standard of care in the United States, even though it has not been shown to improve outcomes in low-risk pregnancies. (It does reduce the number of seizures suffered by newborns, but not to the extent that final outcomes are affected.) Furthermore, EFM has been shown to lead to an increase in cesarean sections. Maternity care patients in particular have been heard to remark with surprise that they seem to be responsible for upholding their right to consented-to care that is also evidence-based. One would think that it would be the provider’s responsibility to offer this care, but … blame the lawyers! In truth, the provider’s hands often are tied – usually by their own institution’s policies or their malpractice liability insurer’s rates.

Frame 11. See Required newborn procedures, above. The mother in this frame is musing on the likelihood of her one-day-old baby being exposed to Hep B by sharing needles with a cribmate.

Frame 12. If you have not yet become acquainted with the Church of the Flying Spaghetti Monster, you can remedy that omission here. Perhaps the strategy suggested in this frame is inadvisable, since a Nebraska Federal District Court declined to recognize FSM as a religion. You can find a lovely stained glass panel representing the FSM here. The story behind an adherent of FSM (a “Pastafarian”) and her successful struggle to be permitted to wear her religious head covering in a state ID photo is documented here.

Frame 12. If you have not yet become acquainted with the Church of the Flying Spaghetti Monster, you can remedy that omission here. Perhaps the strategy suggested in this frame is inadvisable, since a Nebraska Federal District Court declined to recognize FSM as a religion. You can find a lovely stained glass panel representing the FSM here. The story behind an adherent of FSM (a “Pastafarian”) and her successful struggle to be permitted to wear her religious head covering in a state ID photo is documented here.

[Updated July 16, 2016, to add copyright designation.]

[Updated June 4, 2018, to correct case name McFall v. Shimp.]

by Mama

We present an updated graphic that was published on Facebook three months ago. The comments in the middle frame were taken directly from Michigan’s official state website, but were edited for brevity. Unfortunately, the comments are no longer visible on the state website, but some of the comments have been preserved here.

The photo in the last frame is of a young Phyllis Shlafly. To be fair, it was her followers rather than she who are credited with bringing up unisex bathrooms; nevertheless, we put those words in her mouth as authorized by our artistic license.

[Updated July 16, 2016, to add copyright designation.]

by Mama

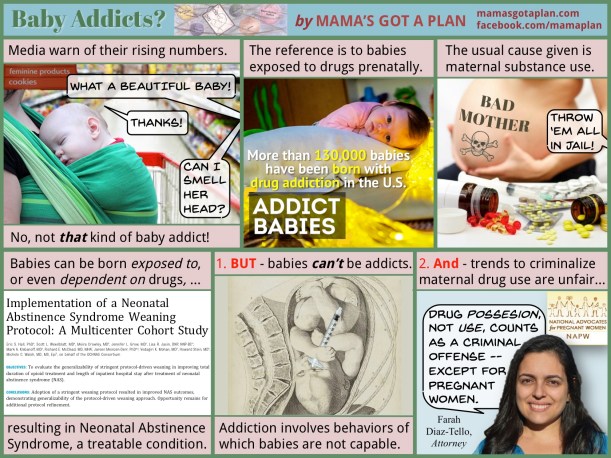

The condition of suffering babies is something everyone can comfortably decry. Sources like the video These Babies Were Born Addicted to Drugs rush to tell us how many babies are afflicted and how worthy of condemnation are their mothers for using drugs – usually opioids – while pregnant. The babies’ symptoms – trembling, shrill cries – are described in great detail. One cannot help feeling that any woman who would subject her baby to such a fate must be a monster.

The only problem is the facts. Babies suffering from Neonatal Abstinence Symptom can and are treated. The symptoms of NAS are often conflated with those of poverty or alcohol and tobacco use. More to the point, to describe babies as addicts is incorrect. Addiction is defined as “a chronic, relapsing brain disease that is characterized by compulsive drug seeking and use, despite harmful consequences.” One cannot accuse babies or fetuses, for that matter, of drug-seeking behavior. Rather, babies whose mothers used substances while pregnant can best be described as drug-exposed or drug-dependent.

To criminalize mothers for their pregnancy outcomes based on substance use is neither just nor effective. Typically, drug possession is a chargeable offense, not drug use. However, in the case of pregnant women, drug use, as determined by drug testing of mothers or newborns, is treated as a crime. Medical providers often fail to inform by their pregnant patients that they are being tested for substances; this is more likely to be the case for those receiving publicly-funded health care. Although health care providers are not permitted to test pregnant people for the express purpose of informing law enforcement, they may nevertheless use maternal testing as a screening mechanism to determine which newborns will be tested. Many states require providers in their role of mandatory reporter to report all such cases to child welfare agencies, who are then free to refer cases for criminal charges.

Prosecuting parents for prenatal drug use is of little benefit. Incarceration is not known to improve the health of pregnant people or their babies. Indeed, while awaiting sentencing in a holding facility, these pregnant people might not receive any health care at all, much less substance treatment. Furthermore, incarceration almost invariably results in the separation of parent and child, an act with far greater negative consequences than most drug use.

Removal of children by child welfare authorities for parental drug use – including legal medical marijuana use! – is not in the best interest of children or parents. Other countries do not automatically assume that drug use renders parents unfit. Determinations of abuse and neglect should be made based on abuse and neglect.

Nor is state involvement equally visited upon the population. Disadvantaged groups, such as poor women and women of color, are more likely to be subject to reprisals based on drug use than are their wealthier white counterparts. However, the fear engendered by medical providers’ role in reporting drug use is sufficient to cause many pregnant people to avoid care altogether – hardly a public health good.

In the 1980s and 90s, media were abuzz with accounts of “crack babies,” children said to have been exposed to crack cocaine in utero. Dire predictions abounded regarding the eventual fate of these children. However, even at the time, it was known that other legal substances – such as tobacco – were much more harmful to fetuses than crack cocaine. Nevertheless, because the crack baby story fed into the War on Drugs initiative proposed by Ronald Reagan – itself a piece of social policy with scant evidence basis – and because it made for dramatic television, it led to severe consequences to many parents and children.

The insistence on condemning mothers of babies exposed to opioids may well be equally suspect. Drug addiction should be treated as a public health issue rather than as a criminal law issue, moves to reduce income inequality and racial bias will do more to aid mothers and babies than incarceration, and blaming women for their pregnancy outcomes will result in less liberty for women in all aspects of their reproductive lives.

[Photos of Farah Diaz-Tello, of National Advocates for Pregnant Women, and Cherisse A. Scott, of SisterReach, used with permission.]

[Updated 6/1/2016, 9:30pm, for grammar and stylistic changes, and again on 6/4/2016 and 9/2/2016. Updated 7/16/2016 with copyright designation.]